By Rob Fiedler

These maps and the accompanying commentary are a follow-up to a previous post based on the work of York University geographer Rob Fiedler. This work explores newly released 2011 census figures for the Toronto Census Metropolitan Area (double click on the maps to enlarge them). Fiedler explains his maps in his own words below and adds some fascinating speculation on possible future development trends in the Toronto region:

“These two maps shown are designed to complement the earlier maps that examined population change (2006 to 2011) at the census tract level.

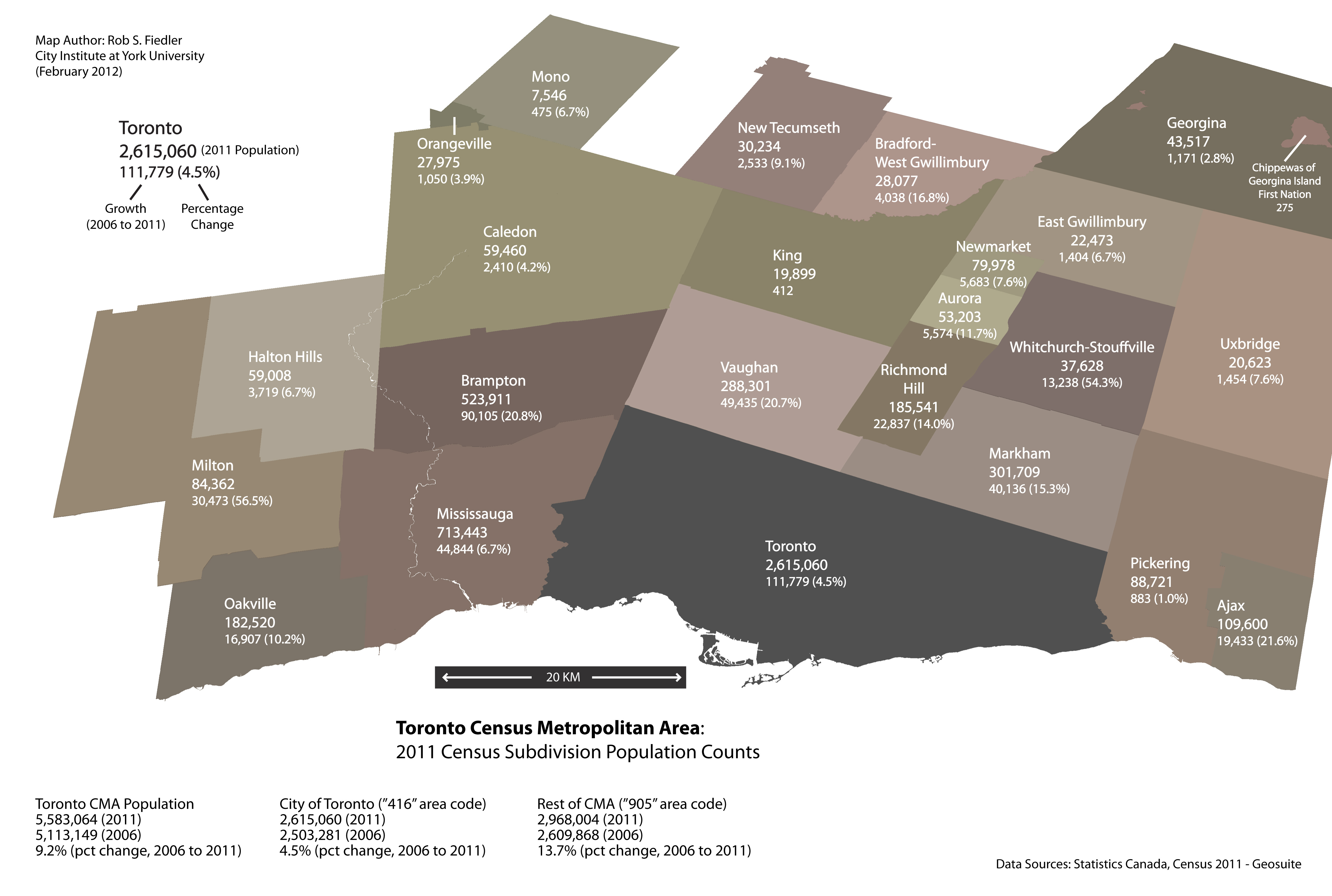

Population Counts and Growth (Rob Fiedler)

The first map shows the population size and population change in absolute and percentage terms (2006 to 2011) of individual municipalities within the Toronto Census Metropolitan Area (Statistics Canada calls these Census Subdivisions). This data is readily available in tabular form, but mapping the numbers allows for easier and faster pattern recognition. At the municipal level the general trend follows a pattern underway since the 1980s: growth in the City of Toronto (locally referred to as the 416 after its telephone area-code) is much slower in the surrounding regional municipalities (905).

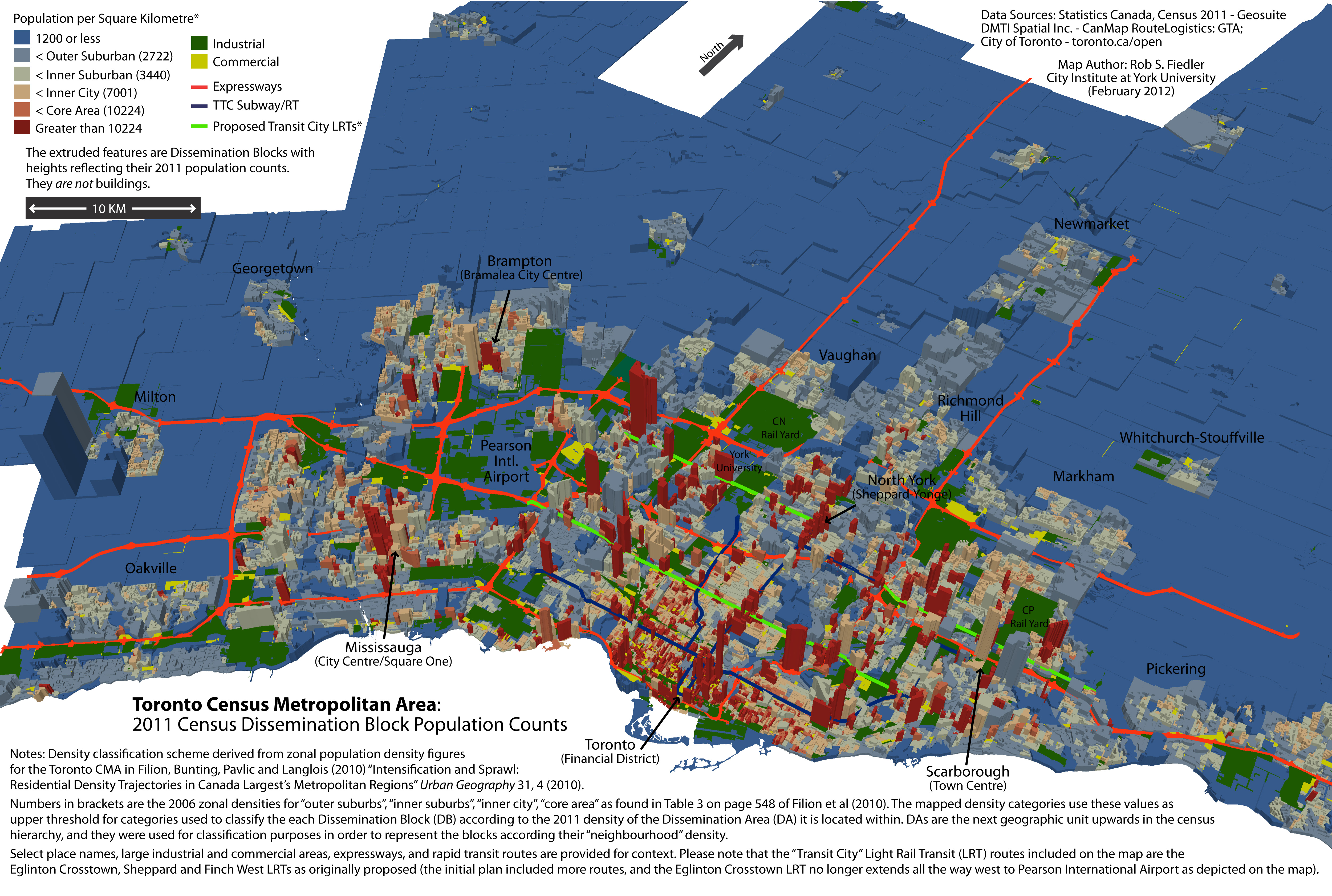

Population Counts and Density (Rob Fiedler)

The second map attempts to provide an alternate perspective by using high-resolution census blocks and select infrastructural and land use symbology to illustrate in a more granular way where the people are -- as opposed to simply populations belonging to jurisdictional units, which may include large areas of that remain either agricultural or exurban. The height or extrusion of the census blocks is determined by their population count, which tends to create spikes where high-rise apartment blocks or condo towers are present. The colour of the census blocks relates to density thresholds drawn from a recent journal article in Urban Geography (see map for full reference and further explanation). Perhaps, the most interesting feature of the map is the way that it illustrates the jump in scale that occurs where vast industrial zones (show in green), large commercially-oriented nodes (shown in yellow), and infrastructural spaces are dominate features of the built environment -- the area around Pearson International Airport, for example. The vastness of these outer suburban areas and the strong presence of land-extensive production and distributional functions within them create difficult connectivity problems for non-automobile based mobility.

Looking beyond the broad trend, more nuanced shifts are evident.

First, after reporting virtually no increase in population 2001 to 2006, the City of Toronto's added 111,779 people, which though moderate in percentage terms, is the largest absolute increase of any municipality in the Census Metropolitan Area (the above-noted previous blog entry points to the role highly concentrated high-rise condominium development as the main contributor to the city's population growth).

Second, beneath the still substantial growth occurring in the big suburban cities of the 905 (Brampton, Vaughan, Markham, Richmond Hill) is a trend toward slower growth rates. % growth since the 2006 census in both Brampton and Vaughan dropped from the low 30s to low 20s, while in Markham and Richmond Hill % growth dropped from the mid-20s to 15.3 and 14.0 respectively. Growth in the largest suburban city in the GTA, Mississauga, continues to fall as greenfield development opportunities wane (from 9.1% to 6.7%). The general slowing of percentage growth in the large suburban cities of the 905 is partly attributable to their already substantial populations since, in absolute terms, they are still seeing significant increases.

The longer-term question that is already faintly discernible in the 2011 population counts is whether the big suburban cities of the 905 are now entering a phase of development similar to what the former suburban members of Metropolitan Toronto (now part of the City of Toronto) experienced from the 1980s onward -- i.e. limited to no greenfield growth, maturation of older residential areas, incipient decline of aging retail/commercial facilities, and erosion of industrial assessment due to wider economic forces. Given the 1980s were also the point at which urban expansion in the 905 took off and industrial development moved north and west in the Toronto region, it is worth asking whether Milton's rapid growth since 2006 is an early warning that history is repeating itself despite the Ontario Government's professed commitment to Smart Growth, urban containment, and intensification?”