By Nishanthan Balasubramaniam

New immigrant settlement patterns are directing newcomers into the suburbs, and as a result, Canadian population growth is occurring in the suburban areas of large metropolitan cities. Suburbs are becoming a mixture of conventional ethnic enclaves and a traditional suburb. Li (2009) has coined the term “ethnoburb” from her study on Monterey Park’s Chinese population near Los Angeles. Li’s (2009) study argues that changes at global, national and local levels have shaped the framework of traditional suburbs. Forces such as economic globalization, shifting immigration policies, and political struggles between and within nations have contributed to a new form of ethnic landscape that goes beyond the traditional definition of inner city ethnic ghettos (Li, 2009). Now this terminology usually applies more to the reality in the United States. It remains to ask, what is its purchase on the Canadian reality.

In fact, I would argue that the City of Markham, Ontario, just to the north of Canada’s largest city, Toronto, can be called an “ethnoburb”. While in the Canadian case the use of this nomenclature does not imply an imagined or real departure from an inner city ghetto of any sort, it does mark a different take on ethnic immigrant settlement than what we knew in the past: densely woven inner city neighbourhoods with a lively streetscape in a traditional urbanist fabric with plenty of cheap housing and entry level (mostly industrial) jobs in the vicinity. Markham is not like that. Instead, it is one of the most diverse communities in all of Canada but it is in a mostly leafy, new and rapidly growing suburban community of 260,000.

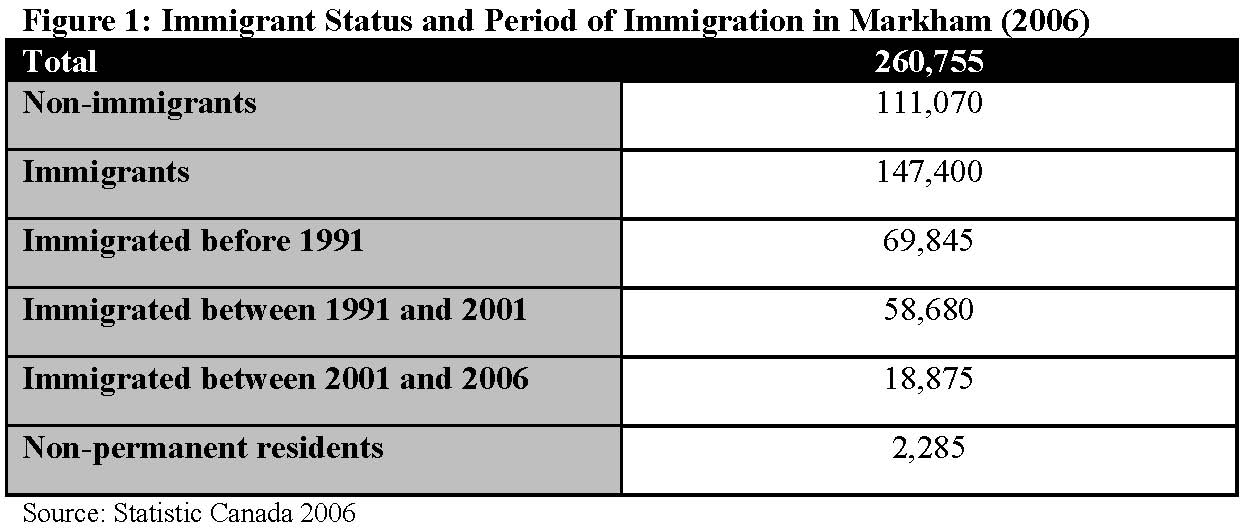

Markham’s Ward 7 and 8 can be described as a multi-ethnic ethnoburb due to the high concentration of Chinese and South Asian populations that share one suburb. My research addresses questions of how Markham can better deliver a wide array of housing options for its residents and how immigrants with local attachments and transnational networks will foster the growth of the economy. In my research, I sought to understand how people with different social and cultural backgrounds and experiences help to shape a multi-ethnic ethnoburb. Figure 1 shows how the dramatic shift in demographics has raised concerns on how to encourage living together with differences. How can we create inclusionary environments for all Canadians?

Most new immigrants and new residents in Markham are from South and Southeast Asia. Within the dominant immigrant groups, there are strong sub-ethnic assemblages who can be characterized as separate entities. For example, the Tamil and Indian populations are similar in many ways; however, they have defining characteristics that can also allow them to be distinguished in different groups beyond ‘South Asian’. This combination of different but strong ethnic groups living together illustrates how Markham is one of Canada’s most diverse multi-ethnic ethnoburbs.

Housing in Ethnoburbia

Markham’s housing stock requires further diversification. Household composition is changing and diversifying and there are an increasing number of smaller households, senior led households, immigrant households and lone parent households looking for more choices in housing types and tenures. The challenge of providing housing is mostly downloaded to municipalities. In Markham, the need for change in the housing composition is urgent in order to better provide a wide selection of housing that is affordable. Markham has a vast and diverse housing stock but most of it in the form of private owner occupancy. The housing supply crisis in Markham has three attributes. First, housing is expensive throughout the entire city. The average price of a single detached dwelling in Markham in 2012 is $580,000 (Wedlock, 2012). Second, there is a lack of rental properties in Markham. In addition, the rental rates are similar to the rates found in the City of Toronto (Preston et al., 2009). Lastly, the larger amount of owner-occupied housing in Markham places a stress on resources for affordable homes for newcomers.

In Markham, the need for change in the housing composition is urgent in order to better provide a wide selection of affordable housing. The change is unlikely to be driven by the private sector and therefore requires policies and incentives established through local, regional and provincial governments. Markham’s high cost of living is placing more and more stress on individuals and families, especially newcomers. City Council must provide developers with incentives for developing a mixed housing stock but must be careful choosing an appropriate strategy. Development charges provide disincentives to multi-residential development and promote the development of single-family homes (Christine Pacini, 2012). This is because the charges levied on multi-family houses are higher than single-family homes.

Diversity, Exclusion, Inclusion

The challenges of diversity or inclusion/exclusion in Markham are illustrated by the Maskid Darual Iman mosque debate. In late September 2011, the Development Services Committee approved a proposal for a mosque; however, the municipality received an influx of emails and phone calls from the public against the development of the mosque. Many of the residents claimed that they were not informed about the development until after the approval was granted to the Islamic Society of Markham. Residents stated that the development would create a parking and traffic problem. Such debate exemplifies the possible divide that is created between different residents of Markham and indicates that exclusion is always looming over immigrants. Some residents acknowledge that the mosque represents a religion while others believe it does not fit the urban form of the community. The development debate was fuelled partially by cultural differences, different planning ideologies, and bigotry.

The mosque development has revealed some of the hidden tension between different groups in Markham. Whether residents’ opposition to the mosque is racist or not, residents are clearly experiencing some discomfort to the changing social, cultural and physical landscapes of Markham. Mohammad Qadeer recognizes that immigrants in Canada choose to congregate together and form neighbourhoods based on their identities (Qadeer, 2004). Qadeer is aware that these types of neighbourhoods may be viewed as ethnic enclaves, communities who segregate themselves from surrounding areas; however, he argues that residential concentration builds ethnic institutions and most importantly, communities. The incorporation of religious institutions into the Canadian landscape is still a complex issue since religion is usually politically sensitive for both the ethnic/religious minority and the host country. Therefore, planning for a place of worship may meet the needs of a particular group, it may also create tensions with others as any kind of development might potentially create. Yet, places of worship have been contentious and have created a positive dialogue in the planning community. With the increase in immigration, planners have to be more sensitive to such tensions.

Transnationalism depicts how globalization is socially constructed by specific social practices that developed transnational networks with immigrant ancestral countries. Thebuilt form of transnational urbanism is where the municipalities and local residents are inscribing new cultural forms in the landscape (Smith, 2001). Transnationalism has provided immigrants with the resources to obtain a successful occupation and have created a comfortable life for themselves. Immigrants have been able to start private businesses, which have helped them become more financially stable. The everyday practices of newcomers shift local economies beyond the approaches of globalization to one that moves culture globally through ethnic economies. Transnationalism has created ethnic economies, which are the most influential force behind the production of an ethnoburb. The businesses are small scale and largely family run, but as the business grows it can employ more members of the ethnic community. An ethnoburb provides a range of specialty products that cannot be found in large retail chains. This niche market demonstrates a connection between ethnic businesses, ethnic households and the neighbourhood. How well ethnic businesses are integrated with co-ethnic suppliers and clients determines the growth of the ethnic service center. Both the ethnic business and the ethnic population depend on each other, and therefore the success of a business is determined by the size of the ethnic population.

Markham must continue to construct transnational developments such as retail centres, community centres and religious buildings because they strengthen the city’s transnational connections. Aiming for the removal of boundaries of exclusion and inclusion, immigrants and existing Markham residents can enjoy multi-ethnic cultures and Markham’s heritage. Transnationalism suggests that the identity of Markham is not one identity but rather the sum of multiple identities. Markham should continue to support multiple or hybridized identities by continuing to provide public ethnic spaces, and by maintaining international connections, and developing new global linkages.

The Future of Multi-Ethnic Ethnoburbs

Markham promotes itself as a multi-ethnic suburb. Spaces for mixed cultural living and socializing alongside new civic spaces and public art aid in its cross-ethnic identification. Residents can relate to space in unexpected and novel ways. Organic developments allow multi-cultures to spread within the urban form of the city. Being open to new and unique ideas, which over time can induce a sense of identity with a place and even come to symbolize the place’s identity. It could be a landmark such as religious site, an open space or a retail centre. Appreciative planning stresses the importance of rethinking how planning issues are identified, conceptualized and prioritized (Milroy & Wallace, 2002). How can planners achieve such rethinking? The role of planners needs to shift towards constructing networks between different cultural groups in Markham and delivering services to support partnerships. Canadian ethnoburbs in the Greater Toronto Area will continue to flourish and expand as new immigrants enter Canada. There are multi-ethnic ethnoburbs/ethnoburbs in Brampton, Mississauga, Richmond Hill, Vaughan, and Thornhill in the Greater Toronto Area and many more throughout Canada. The ethnoburb is still a new expanding phenomenon, and there are several dimensions that require more in-depth research.

Sources:

Li, W. (2009). Ethnoburbs. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press.

Milroy, B., and Wallace, M. (2002). Working Paper Series: Ethnoracial Diversity and Planning Practices in the Greater Toronto Area. Toronto:CERIS.

Pacini, C. (2012). SHS Consulting. Interviewed by the Author. Markham. Mar 16.

Qadeer, M. A. (2004). Ethnic Segregation in a Multicultural City: A Case Study of Toronto, Canada. CERIS: Policy Matters.

Smith, M. (2001). Transnational Urbanism: Locating Globalization. Oxford: Blackwell.

Wedlock, J. (2012). York Region United Way. Interviewed by the Author. Markham. Feb 9.

Photo Sources: Nishanthan Balasubramaniam

This research was supervised by Professor Liette Gilbert in the Faculty of Environmental Studies. The work was affiliated with the Major Collaborative Research Initiative on Global Suburbanisms: Governance, Land and Infrastructure, housed at The City Institute at York University. A major paper of this nature could not be completed without the contributions of Roger Keil and Sara Macdonald at The City Institute at York University. I am grateful for their support and guidance throughout this long process. If you would like to discuss my research further, feel free to contact me nishanthanb3@gmail.com.