By Roger Keil

Raw data. That’s all we want. When one of our research teams conducted expert interviews in the suburban municipalities of Barrie and Markham last year to study their identities in the global city region, one of the first common denominators we detected was the existence of vegan restaurants in both communities. The locations are franchises of an originally Toronto company which has locations along that city’s central axis, Bloor Street, and in New York City. We welcomed the vegan restos as we had a vegan, a vegetarian and a raw food enthusiast in our research team. Lunch was easy that way. But it also made us think about what kind of trend we had come across. Food of this nature is usually not associated with the gritty downtown of an aspiring mid-size city at the verge of the near North (Barrie also boasts being home to The Ranch, Canada’s largest country and western bar, just a stone’s throw from the centre of vegan cuisine) or even with the “Green High-Tech City” ambience of Markham (slogan “Leading while remembering”). As was confirmed in our interviews, almost all stereotypes of urban versus suburban had to go out the door as we spent more time in the ‘burbs. Clearly, there are many differences between downtown living and suburban living, and mind you the latter does still exist in its subdivisioned glory! But to make assumptions about who eats, consumes, thinks or does what in each place was just that: a presumptuous way to go about understanding the world. Vegan restaurants are not the purview of a select few huddled around trendy hoods in the inner city. They do, in fact, serve a more diversified clientele in the entire urban region.

Much of that came back to me when I read that now famous New York Times post by Alex Williams on an allegedly emergent “hipsturbia”. I wasn’t surprised by either the piece, which I found quite amusing, and the reaction to it. More on both below. In fact, I had just put the finishing touches on the introduction to a book I am editing on Global Suburbanisms which is published by Jovis (Berlin) later this year. Without giving too much away, I can share that I had just picked up on the trend noted by Williams, albeit with a different intention altogether: I picked the suburbanization of New York and of New Yorkers as a prime example of the myths we have to dispense with when we look at the urban revolution today, which in fact is more of a suburban revolution.

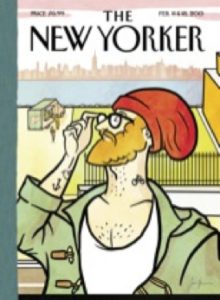

I took note of the February 2013 anniversary issue of The New Yorker, perhaps the most iconic downtown publication around. It shows a “Williamsburg hipster,” the defining indicator species of gentrifying urbanity, on the other, suburban side of the river (or perhaps on Liberty Island, at the foot of the Statue of Liberty), separated by water, with only a faint reference to the skyline of Manhattan. A suburban take on the classical New Yorker dandy who also wears the hipster’s red cap that could as well be mistake for the bonnet de coton of the French revolution. I asked myself: Will the Right to the City have to be claimed once more from the far bank of the river? And perhaps from even farther afield in the (sub)urbanized region?

At around the same time, Ralph Martin, an American living in Berlin related how, after the fall of the Wall, fellow Berliners fanned out into the Brandenburg countryside’s and took temporary root in its quaint small towns. While the Berliners soon caved under the pressure of their less than friendly country neighbours, the trend can be understood as the blueprint for the New York urbanites’ alleged exodus from Brooklyn to the exurban towns of Hudson and Beacon. Their quest for “country cool” bohemia is prompting the “Brooklynization of Upstate New York.

At around the same time, Ralph Martin, an American living in Berlin related how, after the fall of the Wall, fellow Berliners fanned out into the Brandenburg countryside’s and took temporary root in its quaint small towns. While the Berliners soon caved under the pressure of their less than friendly country neighbours, the trend can be understood as the blueprint for the New York urbanites’ alleged exodus from Brooklyn to the exurban towns of Hudson and Beacon. Their quest for “country cool” bohemia is prompting the “Brooklynization of Upstate New York.

This corresponds with Alex Williams who discovers “cosmopolitan bohemia … along the Metro-North Railroad, roughly 25 miles north of Williamsburg, Brooklyn, in the suburb of Hastings-on-Hudson, N.Y.”. Of course, you guessed it, Williams also finds a “gluten-free bakery” and a “farm-to-table restaurant”, close cousins to the raw food vegan temples of Barrie and Markham. Williams has been criticized and ridiculed for taking anecdotal hearsay for fact and for being blind to the statistical trends of increased poverty in the suburbs: “American suburbs are not becoming hipper and younger, but are in fact becoming poorer as young adults with economic means increasingly choose to live in cities), browner (as immigrants and African Americans are priced out of central urban neighborhoods), and grayer (as the suburban population ages).” And of course there is no limit to sarcasm once hipsters have been wounded and the New York Times smells like it has fallen to the allure of sensationalism. And, indeed, there is reason to believe that the hipsters are ultimately just another wavelet that adds to the traditional tsunami of white privilege in that area.

Whether we think the whole hipsturbia thing is a hoax or just poor journalism doesn’t matter. But there is something that is relevant in this story, which is that the hipster theme just serves as a screen onto which our common prejudices are being projected. What bothers me about the debate is the essentializing of city and suburb that continues to determine our thinking. Rather than putting the story into perspective of a larger (sub)urban revolution in which multiple urban ways of life exist across an urban revolution, both the proponents of a Brooklynization of suburbia and their detractors seem to have little problem with keeping intact the exact categories that have become fluid: city and suburb.

Whether we think the whole hipsturbia thing is a hoax or just poor journalism doesn’t matter. But there is something that is relevant in this story, which is that the hipster theme just serves as a screen onto which our common prejudices are being projected. What bothers me about the debate is the essentializing of city and suburb that continues to determine our thinking. Rather than putting the story into perspective of a larger (sub)urban revolution in which multiple urban ways of life exist across an urban revolution, both the proponents of a Brooklynization of suburbia and their detractors seem to have little problem with keeping intact the exact categories that have become fluid: city and suburb.

Hipsters are creating their own hype. This is mostly due to the fact that the hip classes are also the chattering and scribbling classes. This has been the case as long as there have been modern bourgeois elites in cities, and it has recently been enhanced as the creative classes have taken control of the levers of public opinion in urban contexts. Hipsters, in many ways, are the most obnoxiously visible sign that one has arrived in a neighbourhood that is considered creative. Now this is not about the creative class, what it means and who belongs. This has been discussed elsewhere at length. What I am concerned about is the closing of options for understanding the tremendous changes our urban regions experience if we keep seeing those changes through the eyes of existing tired socio-economic and socio-spatial categories.

Yes, we must beware of any new forms of gentrification and privilege that endanger traditional communities, and we must fight emerging and pernicious forms of segregation and ghettoization (as we have seen more often than not in the peripheries of cities lately). But to do this must not allow us to sit back in a conceptual armchair from which we see the (sub)urban revolution sweep urban regions. The alleged inversion of the urban and the creative, and above all of hipsterdom, for example, can only surprise those who believe that we still live in a sectoral, if not concentric, urban world where all urbanites return demurely where the come from, where you have dichotomies and polarized functions that need certain spaces for them to be performed (work=city; live=suburb or city=hip; suburb=boring). In fact, we must not allow ourselves to fall back behind what many who have grown up in, or have lived in the suburbs intuitively understand: the suburbs are not a caricature of homogeneity. As Ian Balfour has pointed out, The Arcade Fire, the leading hipster band of the last decade, and creators of the superb album The Suburbs have made that point clear. Theirs is not “the snotty downtowner’s view of the impossible banality of the suburbs, the sort of posture that imagines Philistinism to permeate the water like fluoride” (Balfour 2011: 157).

Mainstream researchers have told us for a while that it is not just hipsters that are on the move. In the United States, the classical land of white middle class tract housing suburbia, significant change is under way. The suburbs are becoming less middle-class and more non-white and immigrant. Alan Ehrenhalt (2012: 6) notes “the most powerful demographic events of the past decade were the movement of African Americans out of central cities… and the settlement of immigrant groups in suburbs, often ones many miles distant form downtown”. Richard Florida, usually in defense of the “creative” core, has admitted that:

"It’s not just our cities and urban cores that are changing; our suburbs have, too—and to such an extent that the very categories of urban and suburban are becoming increasingly outmoded. More and more suburban households are made up of singles, empty nesters, or retirees. Even families with children are seeking a more compact, less sprawling, less car-dependent way of life. ... But at their best, cities and suburbs are coming to look more and more alike—suburban shopping districts are walkable and rich with amenities like cafés and galleries; urban "strollervilles" are filled with young families. The most successful suburban and urban neighborhoods both have good transit, mixed uses, and green spaces; most important, they foster the interactions from which vital communities are built."

Where Florida sees urbanity, opportunity and growth, others see crisis, gentrification and social segregation as well as rising poverty. Researchers at the University of Toronto, for example, have recast the inner suburbs of that Canadian city as a racialized “Third City” of increasing poverty, insecure tenancy and new immigration status (Hulchanski 2010). The conversation on the suburban has turned from its role as a derivative and substandard, even pathological form of modern living to a place where worlds collide, where futures are made, where urban change has to be explained.

It should not surprise us then that we find yoga and young people in the suburbs. Nor should it surprise us when we find increasing poverty and service deficits in areas where the market traditionally took care of everything, most extremely in the form of exclusionary privatized utopias.

The suburbs are normally just the equivalent of the rapidly changing inner cities. Both, and everything in-between, follow a deafening and disorienting pace of restructuring which serves the needs of a resurgent post-crisis economy where new investments flow to any crevice cracked open in the last crash. This includes, sometimes first in line, the devalued ruins of the previous crisis. Small wonder, then, that even Pontiac, Michigan, gets its share of “suburban renewal”.

What are the perspectives for progressive thought and politics in all this? The impetus for progressive politics and living and for different forms of urbanism not classically connected to the “inner city” is by no means new and it is not impossible. Major progressive communities of the 1980s, like Santa Monica and West Hollywood in the Los Angeles area or even Burlington, Vermont, were hotbeds for radicals, tenant activists, more or less closeted socialists, gay pioneers and the like but they were also, by and large, suburban (Keil 2011). Not all is lost if the hipsters move out of their myopic environments. The move of the perceived ‘cool’ to the ‘country’, or at least to the ‘burbs is not unique to New York anyway. Paris is feeling it. Toronto has long been the location of the happening periphery.

Let me, then, lastly say something in the defense of the common hipster, who seems to be unduly pushed around by everyone who has a blog and then some. In my decidedly unhip youth, hipsters were those who knew what was in the new issue of the New Musical Express before it even came out. Now one observer equates the hipster with “educated white folk” which is probably true if you take the Portlandia species of hipsterdom as the measuring stick for the entire breed. But it must be said that in cities like Toronto with its majority immigrant population (and perhaps London, New York, Berlin, what have you), the hipster now comes in all kinds of shades. The Ethnic Aisle (if I may borrow this term in this specific use from the wonderful project by the same name), in fact, is full of them as are the remarkably mixed bars of Queen Street West in the Canadian metropolis. We may find then, that the tattooed punk-rocking, vegans and hip-hoppers who crowd the yoga studios of the suburbs and small towns of the expanding urban regions in many parts of North America may actually be more diverse than most observers would admit. What makes a hipster is as moveable a target as are what is suburban.

Literature:

Balfour, I. (2011). Suburbs of the Mind. Public 43.

Ehrenhalt, A. (2012). The Great Inversion and the Future of the American City. New York, Alfred A. Knopf.

Hulchanski, J.D. (2010). The Three Cities Within Toronto: Income Polarization Among Toronto's Neighbourhoods, 1970-2005. Toronto: Cities Centre, University of Toronto.

Keil, R. (2011). Suburbanization and Global Cities. In B. Derudder, M. Hoyler, P.J. Taylor & F. Witlox (eds.) International Handbook of Globalization and World Cities. London: Edward Elgar.

2 comments on “What’s with all the hype about hipsturbia?”