By Jean-Paul Addie and Roger Keil

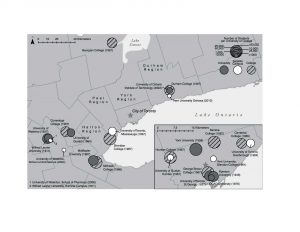

Toronto is a university town. But more and more, the weight of student numbers shifts out of the central city into the sprawling Canadian metropolis’s burgeoning sub- and exurbs. Clearly, the importance of the centralized campuses of the University of Toronto, Ryerson University and OCADU is not waning. However, York University’s presence, the branch campuses of the University of Toronto in Scarborough and Mississauga as well as the many colleges across the region’s suburban expanse, are beginning to shift the quantity, if not the quality of some of the higher education complex away from the inner city into the rapidly growing inbetween cities and cities in waiting outside. Toronto’s post-suburbanization raises unprecedented opportunities and profound challenges here, both in terms of changing expectations of higher education and where in the world – and the city – university adaptions need to proactively unfold.

How does university regionalism happen and what are its consequences?

Following some SSHRC-funded research we have done with Kris Olds at the University of Wisconsin, we have found that the relationships of cities and universities are more complex than the old “town and gown” simplicity seems to suggest. Universities and cities both negotiate complex social and spatial relationships and interact as self-interested actors. Sometimes their strategic goals align and sometimes they do not. “Town and gown” relationships are further muddied as they play out in sprawling and globalized city-regions, such as Toronto.

In contrast to smaller, single-player university towns, the Greater Toronto Area has long supported a more complicated higher education system. Multiple higher education institutions (of varying sizes and with differing mandates) have provided an assorted suite of teaching and research services to met the needs of a diverse set of stakeholders; from undergraduate and continuing education students to local and national governments and the private sector. The late-1950s to mid-1960s witnessed a wave of higher education metropolitanization in Toronto. Ground-breaking at suburban university and college campuses, in addition to the founding of new universities in the Kitchener-Guelph-Waterloo region, embedded academic institutions within the spatial Keynesian projects being pursued by the province and Metro Toronto. These institutions not only provided educational opportunities for Fordist workers and their children, but also remade the Fordist metropolis itself, notably serving (and continuing to serve) major student populations beyond the city core.

Just as southern Ontario’s mid-century era of university expansion belied the social and spatial growth of the Fordist-Keynesian metropolis, an incipient post-2000 wave of (predominantly specialized) satellite campus developments sweeping across southern Ontario discloses a new geography of urban and higher education restructuring. Here, we see universities and urban actors pursuing a variety of strategic objects that now respond to, and actively reshape, the Toronto global city-region.

Universities have emerged as key players. Universities are falling in line with elite strategies elsewhere that create infrastructural bypasses around “costly, slow and inefficient” local institutional needs and expectations to cater instead to a globally constructed market place for student intake, teaching personnel, administrators on one hand and research excellence on the other. Higher education institutions contribute actively to supra-local channels of teaching and research that “put them on the map” in the ever widening spectrum of institutional offerings that now range from fireside chat type first year tutorials to massive open online courses; the so-called MOOC’s that assemble thousands through virtual lectures and seminars. Universities have been hyper-busy carving up the globe. Like a latter day William Pitt and Napoleon, universities (often operating in consortia) slice India or China or Africa into digestible pieces for consumption through student recruitment, research partnerships or commercialization activities.

Universities have emerged as key players. Universities are falling in line with elite strategies elsewhere that create infrastructural bypasses around “costly, slow and inefficient” local institutional needs and expectations to cater instead to a globally constructed market place for student intake, teaching personnel, administrators on one hand and research excellence on the other. Higher education institutions contribute actively to supra-local channels of teaching and research that “put them on the map” in the ever widening spectrum of institutional offerings that now range from fireside chat type first year tutorials to massive open online courses; the so-called MOOC’s that assemble thousands through virtual lectures and seminars. Universities have been hyper-busy carving up the globe. Like a latter day William Pitt and Napoleon, universities (often operating in consortia) slice India or China or Africa into digestible pieces for consumption through student recruitment, research partnerships or commercialization activities.

At the same time as universities play the global game, they engage in identity formation as they seek to style themselves into “local universities”, tied firmly into and being strongly supportive of neighbouring communities (whether that is the medical-industrial complex downtown or the less economically fortunate but demographically diverse tower blocks around the universities in the suburbs). In some cases, universities are directly active in – often well meaning, yet somewhat colonial – place making exercises and social engineering in what is considered socially needy neighbourhoods at the periphery of campus. At the other end of the place-making spectrum, most universities have drunk the high tech Kool-Aid and take part in deliberate network building among firms in that sector that have specific research needs. Universities have themselves intensified their efforts in planning for lands they own in their proximities as is the case in York University’s “Lands for Learning” initiative. In some cases, universities have begun meaningful work with surrounding welfare organizations to look after those left behind in the frantic push for neoliberal profiteering and rent seeking.

There are clear hierarchies and pecking orders. As the picking winners model of university competition seems to favour the bigger and more well endowed research institutions that receive huge funding for engineering, science and medical research, the less fortunate institutions lower on the food chain and more invested in the humanities and social sciences try to overcome their deficits and hold on for bare life through investments in niche and specialty programs. When there is no chance to have a medical campus, why not try health as a viable alternative?

There are clear hierarchies and pecking orders. As the picking winners model of university competition seems to favour the bigger and more well endowed research institutions that receive huge funding for engineering, science and medical research, the less fortunate institutions lower on the food chain and more invested in the humanities and social sciences try to overcome their deficits and hold on for bare life through investments in niche and specialty programs. When there is no chance to have a medical campus, why not try health as a viable alternative?

Lastly, in this list of possible university-city-world relationships, teaching institutions have come to consciously reflect the region. When, as is the case in Toronto, for example, the going motto says “diversity is our strength”, universities make that their very recipe for success both in their local home-environment and in their global aspirations.

Municipalities as players: The city side of the town and gown equation rather directly reflects university policies of growth and investment in a global environment. Cities have made huge strides and a broad range of attempts to insert themselves into the overall strategies of competition in the global city-region. Having first class universities is pursued in similar ways (yet with more pronounced language of creative economies) as cities have gone after sports arenas and cultural temples in the past. In this scheme, universities are part of the expected infrastructure of “cities in waiting”. For the Toronto suburbs and some mid-size towns in the region, embracing their immigrant diversity and nurturing those communities’ external economic relations abroad has provided a foundation to emerge as newly confident players in the search for identity in the global city region. Universities play a big part in this process.

Some small or midsize suburban and rural municipalities are beginning to view universities as important assets in building their own identities in a game of global competition among regions. In this game, it is not just the central city that determines the conditions of the intra-regional processes of local identity building. Toronto is just one, albeit the largest regional city, that makes its presence known on the international stage. Others, specifically the immigrant ethnoburbs such as Mississauga, Brampton, Vaughan, Markham but also Barrie farther to the north are forging their own identities and policies to have a position in the globally scaled game of intermunicipal competition. Rather than vegetating in some undefined hibernation of suburbanity, those communities are demonstrating their appetite for change: they are becoming a destination and attracting an institution of higher education is one of the signposts towards that goal.

The prospects for the regional university landscape

Ontario (along with British Columbia and Alberta) is going to be the exception to the precipitous fall in numbers in Canadian university age population over the next generation (despite the country’s predictably stable intake of a quarter million immigrants each year for the foreseeable future). And it can be assumed that many if not most of the late teens and twenty-somethings that are likely going to populate the province’s campuses are going to live in the suburban communities to which their parents have been moving in the past twenty years. Projections are difficult but all scenarios seem to point towards the importance for Ontario (and especially Toronto area) universities to be prepared for a continuous stream of university applicants. Most likely, this population will also be even more diverse than the university attendants in the past. Both universities and municipalities are beginning to make plans for these scenarios.

Vaughan: Vaughan Mayor Maurizio Bevilacqua offered his city as a possible location for a York University expansion campus to the institution’s president Mamdouh Shoukri at a business luncheon in February 2014: “We consider ourselves very much tied to York University. We are from York Region, after all. And so, as you contemplate a new site for a new campus of York University, on behalf of the over 500 people that are here, … I want to really ask you to consider our city for a new campus.” The plea was not accidental. Bevilacqua is a York graduate himself, and his municipality borders the northern edge of the suburban university’s sprawling campus, home to more than 60,000 students. It was also not a big surprise as the mayor’s pitch met a prior expression of interest by the university to expand north with a branch facility.

Shoukri on his part has led the expansion effort which itself is a reaction to a provincial “Call for Proposals by the Ministry of Training, Colleges and Universities to increase student capacity in areas of growing demand for postsecondary education”. A short list of Markham, Richmond Hill and Vaughan has been drawn up and a York University proposal to the province is expected for September 2014.

Barrie: North of York Region, in the near North of the County of Simcoe, the city of Barrie has also launched a campaign to bring a university campus to what is billed the largest city in Canada without such a facility. The target for Barrie, presently home to a college campus, is Sudbury based Laurentian University which has already stretched its tentacles southward and is growing its operations there. The municipality, led by the charismatic mayor Jeff Lehman, is welcoming the Laurentian expansion with open arms and says that the city is “university ready”. Barrie’s high-flying hopes are being kept in check by competing proposals from other municipalities such as the western Toronto suburb of Milton.

Outlook and Conclusion

The extension of universities into Toronto’s post-suburban frontiers presents significant potential to mobilize academic knowledge, forge new paths for public engagement by, and with, universities, catalyze local economic development and open access for non-traditional students, including the immigrant, visible minority and working class communities who increasingly make their home in Toronto’s inbetween cities.

Yet municipalities’ desire to leverage the economic impact of the “entrepreneurial university“ should be tempered to a degree. When the luster of courtship fades, universities have not always embraced leadership roles in their communities; particularly when their strategic interests diverge from those of their municipal hosts. Branch campuses, both locally and globally, have produced mixed results while the local capture of commercialized academic knowledge does not simply align with geographic proximity. Those seeking to replicate the relationship of Stanford University and Silicon Valley, even on a small scale, shouldn’t be surprised if the latest tech Mecca fails to materialize on the shores of Lake Simcoe or straddling Highway 7. Moreover, despite claims of universities’ local economic impacts, the skilled nature of much academic labour means many place-based employment opportunities are likely to be cleaning modern, spacious labs, rather than utilizing these facilities to launch new start-ups and spin-offs. The multiplier effects of university engagement may well result in incoming students claiming new service jobs in the coffee houses and bistros that often accompany the local rise of university-led knowledge economies.

This isn’t to say that the arrival of a university campus the latest doomed solution for municipalities looking for an economic development fix. Rather, the university-city relations in the global age need to be carefully marshaled. Contra to the assumed policy wisdom of university-led urbanization, bullish campus expansion programs attempted by University College London (at the Olympic Park in Stratford – Europe’s largest regeneration site) and New York University (into the East Village) have been met with strong opposition; not only by local residents, but by university faculty and staff. These may be major university players operating in primary global cities, but their experiences (and necessary need to learn from ambitious missteps) hold an important lesson for university regionalism in post-suburban Toronto. Universities, just as the cities and neighbourhoods in which they locate and act, cannot be considered as singular, homogenous entities. Being “engaged” can mean different things to different actors on both side of the city-university divide. Disaggregating “town” and “gown” opens new avenues for collaboration and network-building and deepens our understanding of the evolving relationships between academic and urban communities. Developing from this, engraining broad and multilayered civic agendas within the spatial strategies of universities is a vital first step. There is encouraging evidence of universities, at the administrative level, developing R&D synergies with suburban municipalities and engaging immigrant organizations in “ethnoburbs” and community, environmental and labour groups as key partners. But this shouldn’t overlook the significance of civic engagement and interpersonal relations forged by research institutes and individual faculty, students and researchers on a day-to-day, ground-up basis. These linkages – the multifaceted social relations and soft infrastructure of contemporary “town and gown” dynamics (rather than physical campus developments) – are the foundations upon which lasting and mutually beneficial relationships for new urban universities and post-suburban communities can, and ought to be built in the global city-region.

Jean-Paul Addie is Provost Fellow at STEaPP, University College London.

Roger Keil is a professor of environmental studies at York University.